Unveiling the Unseen: Navigating Obstacles and Opportunities on the Way to College–Part 1

Today I bring you another triumphant story of someone who grew up in a Plain community where education was used as a means of social discipline and how she found her way to college and beyond. The joy is obvious in Naomi’s story of how she thrived with an education designed for self and professional development. This story will be published in two installments.

By Naomi Clark, PhD

Literacy is foundational for human flourishing–in the 21st century, more than ever. Yet, as those of us attending this Symposium know from experience, access to education is not guaranteed for everyone.

Deborah Brandt is a scholar in my field (English) who gives other writing studies scholars a way to talk about how economic forces influence the way individuals learn to read and write and how this is related to the way a society values literacy. To do this, Brandt invites us to think about the individuals or groups that help a person become literate. Brandt calls these agents or entities “sponsors of literacy.” They can be anyone who teaches, supports, or even controls our literacy. What is key to this concept, though, is that these sponsors are ultimately benefiting from our literacy (or lack thereof) in some way.

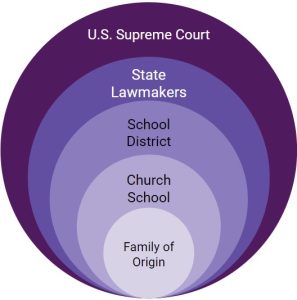

When I think about how this concept of sponsors of literacy applies to my educational path, I imagine my sponsors of literacy as concentric circles:

Family of Origin (innermost circle), Church School, School District, State Lawmakers, U.S. Supreme Court

This framework prompts me to ask these questions:

- How did each of these entities influence my educational options?

- What literacies did they open up for me?

- What barriers to literacy did I encounter?

- How did they (and the segment of society they represent) benefit from the status quo?

I will use the first three questions to frame my own academic journey.

Family of Origin

One of my earliest memories related to literacy was when I was about five years old and I was begging my mother to teach me to read. I was born into a family that prioritized books and reading, and I desperately wanted to crack the code that would let me in on the fun. First grade seemed light years away, and I didn’t want to wait. My mother taught me how to spell my name along with a few basic words. I practiced writing them on every available surface.

(As a middle child, I couldn’t decide if “big” or “little” best described me so I went with both.)

My mother was raised in western Maryland where she attended a one-room school through seventh grade, then had to stay home because of health issues. Years later, well into her twenties, she attended LPN training at a technical school. The year she enrolled was the last year they admitted students who hadn’t completed high school. She finished near the very top of her class.

My father was raised in central Pennsylvania where his formal education ended at eighth grade. Later, when he was 17, he taught school for a year or two in a local two-room Amish Mennonite school. He was ordained as a Beachy Amish minister in his twenties. His only formal ministerial training was when he and my mother packed up the family and took us to Calvary Bible School for three weeks one year.

When I finally got to school, I thrived in first grade. While my older sister attended school in the church basement, my class of 10 first graders met in a house trailer on the church property. Under the influence of Bill Gothard’s Institute in Basic Life Principles, the following year my parents decided to homeschool my siblings and me. We used an earlier version of ACE, a Baptist curriculum that was distributed by Amish Mennonites. I even became a poster child for the curriculum, along with my older sister and younger brother, when our photo was used in a promotional brochure for the curriculum.

Naomi at age 7

Church School

For 7th grade, I begged my parents to let me attend the church school; they finally relented. I was bored and lonely at home. Anyone well-acquainted with middle schoolers will not be surprised to hear that I was soon bored and lonely at school too. However, attending the church school put me on the path to high school which I finished just before my 16th birthday.

This achievement doesn’t sound nearly as impressive when we take a closer look at the school environment. My high school experience likely had more in common with an eighth-grade Amish education than with that of a standard public-school education. The curriculum was designed as self-paced booklets. Students worked independently through countless pages of fill-in-the-blank rote learning that involved minimal interaction with teachers or peers. There were no science labs, and the options for high school electives were typing, Bible, Spanish, and a computer science course from the 1970s. Recess counted as PE credits even though we spent most of our free time in winter playing table games. Many of the teachers had 8th grade educations and the principal was a Beachy Amish minister. (To flash forward for just a moment– once I was finally applying to college nine years later, I had to request a transcript multiple times, and when the official transcript finally arrived, I believe it was type-written on something like an index card.)

What literacies did this education open up for me and my classmates? Through the rote learning, we learned that there was one right answer to every question. We learned to check boxes and follow directions. In contrast, skills that would have expanded our range of options as adults (skills like learning the scientific method, how to write a research paper, advanced math, public speaking, or how to socialize with people outside our community bubble) were not prioritized.

There were four of us in our graduating class of 1992. We were all nerdy overachievers who would have thrived in college, but college was simply beyond our frame of reference. I was intrigued by the dream of college but had no idea how to get there. All I knew was that college was very expensive and that my family didn’t have anything to spare. My elders ignored any talk of college and I overheard peers mocking me for it. I may have had a high school diploma, but I had no better understanding of how to get to college than how to get to the moon.

School District and State Lawmakers

By the time I graduated from high school, my parents had adopted several youngsters, some of whom had behavioral and developmental needs that the church school did not have the resources to adequately support. Once I was home, they decided to switch back to homeschooling the younger ones. By this time, Pennsylvania homeschooling laws had changed to require homeschooling parents to have a high school diploma or the equivalent. My parents didn’t have either, but I was at home and I had a high school diploma. So we took my diploma down to the school district office. I still remember a remark that one of the administrators made when we asked if my diploma would suffice. He barely glanced at it saying, “Yeah, well, the Amish aren’t held to the rules anyway.”

Supreme Court

Whether or not that school district official was aware, the Amish hadn’t been “held to the rules” since the U.S. Supreme Court decision Wisconsin v. Yoder (1972) that effectively denied Amish and Mennonite youth access to education, something considered a human right in virtually any other part of the world. This ruling (by individuals representing the most educated and privileged social classes in the nation, no less) has been a major influence on the formal education available to children like me in Plain communities ever since. It established the horizon of what I could dream of or aspire to in a culture where the highest praise a young woman can receive is Eine Tag machst du ein Mann eine gute Koch. (“One day you’ll make some man a good cook.”) While specific communities, congregations, teachers, and families may still take formal education seriously, this ruling effectively prevented any safety nets or minimum standards in Plain communities where formal education is considered a necessary evil or a waste of children’s time. Thus the Supreme Court’s ruling green-lit and even normalized educational neglect in Plain communities under the guise of “cultural sensitivity” and “religious freedom.” Each subsequent circle of my literacy sponsors also played a part within these boundaries to shape the educational options available to me as a child and teen.

Significantly, much of the power of literacy sponsors is in their unobtrusiveness in our daily lives. As part of the wallpaper, so to speak, representing institutions and practices that go unquestioned, we risk mistaking their influence for our own inherent qualities. For example, through the interplay of my sponsors of literacy, I finished high school with no confidence that I was capable of college. It was easy for me–or any other Plain child–to doubt myself and my intellectual abilities even though they were hardly the reason for the limited educational opportunities available to me.

Looking Back to Move Forward

What I personally find most transformative about this concept of sponsors of literacy is that shining a light on these influences on my childhood education empowers me as an adult to determine my literacy options going forward. That is, as we as individuals become aware of the public policies and institutions that determined our educational horizons, we simultaneously realize that it was not necessarily a lack of intelligence or lower IQ or subpar work ethic that limited our options in life. This realization opens a path for us to take greater ownership of our learning in adulthood. As many of us have learned, we actually could succeed and even thrive in college and in professions that college education opened up for us. As I came to discover, my educational journey was not limited to these concentric circles. Taking ownership of my literacy in adulthood greatly expanded my opportunities for personal growth and professional development.

To be continued.

How an Amish Boy Became a Physicist, Part 1

Today I bring you the amazing story of Leon Hostetler’s educational journey that took him…

To order a signed copy of my book(s), click on an image below. You will be taken to the books page of my author website to purchase.

Thanks so much for sharing these life stories.

And thank you for reading!

I had no idea that the IBLP reached into plain communities. Thank you for the information.

Yes, it runs the gamet from enthusiastic devotees to those who want nothing to do with IBLP, but its influence is definitely there. Thanks for reading!

The last comment of ” sponsors who may benefit from literacy or lack thereof” really got me thinking. Have you read (i’m not sure the name of author I think it was something like schmidt) who lived in a Canadian Russian Mennonite community that discouraged education. Literacy frustrated him until he realized he was dyslexic. Then in analyzing his community he realized that probably many of the leaders of his community were probably also dyslexic which led them to discourage education. Because they didnt want to be humiliated by people who were “smarter” than they werel and thinking of the Mennonite community that I spent my teen years in there was a long history of discouraging education. But then many of the older adults had had to navigate switching from German to English (and learned to speak English when they went to first grade) that they probably never really learned to have a good grasp on English grammar. just my thoughts. so again they could have great theological deep discussions in Pa. Dutch but were lost when it came to doing it in English. So it was just easier to restrict what the kids read .

That’s an intriguing perspective, Shirley, and it makes a lot of sense to me. I think dynamics like these within cultures make it very easy to emphasize one kind of intelligence over another and soon it becomes the norm. That said, the deliberation in Wisconsin vs. Yoder makes it very clear that the motivation of Amish leadership to keep Amish children out of high school was to limit their options and keep them in the community. I can see how combining multiple factors like these can all work together to create a negative attitude about education.

I’m not familiar with the Canadian Russian Mennonite author you mentioned, but I’m very curious now! Thanks for reading and commenting!

Shirley may be referring to the book, The Brilliant Idiot An autobiography of a Dyslexic by Dr. Abraham Schmitt. I read it years ago, so I might be remembering incorrectly and she might be referring to a different book.

[…] Today I bring you the second half of Naomi’s story. You can read the first part here. […]