Stepping off the Tightrope: A Journey of Faith, Struggle, and Redemption

Today I bring you Part 1 of a story:

By Marilyn Coblentz

I was born in the hollows of Virginia. My parents met at a children’s home on the other side of the mountain and when they got married and started raising their young family, they chose to stay with the church community there. In those days, Amish and Beachy youth did voluntary service, and this children’s home was an option available to them. Many in this church, like my mother, had left the Amish in search of a new understanding of God and faith. The church I was born into was under the Beachy Amish umbrella but operated with a strong Amish influence.

Marilyn, age 5

It wasn’t until much later in life that I realized how often we make lateral changes, believing they are vertical. Lateral changes don’t challenge our thought processes, rather they allow us to stay comfortable and justify our actions, especially when we believe these changes are God-ordained. Many practices of this tight-knit congregation were very Amish in nature but were presented with much more conviction and certainty that every move was God-ordained.

My mom was raised in an Old Order Amish community in Sugarcreek, Ohio. She was the oldest of nine siblings and was the first in her family to leave the Amish church. This departure brought grief and disruption to her family. Although there was talk of disinheriting her, for some reason it never happened. My sense was that my parents believed they had prayed and walked in a godly enough fashion that God changed the hearts of her parents and family. I don’t think anyone ever paused to consider that perhaps love and grace were involved on the part of my grandparents; maybe it had little to do with my parents’ belief that they were perfectly in tune with God.

My dad was raised and baptized into a conservative Beachy Amish church in central Pennsylvania. He had a re-conversion experience at this church in Virginia and was re-baptized. This re-conversion, re-commitment, re-baptizing would be something that would follow many of us as we navigated life; we kept trying to somehow get it right this time around.

In the 1960’s, the Beachy Amish belief system was one step away from the Amish. They considered themselves a bit more “saved” than their Amish families and ancestors, believing they had a better understanding of the Bible and God. While the Amish merely had a “hope of salvation,” the Beachy Amish were proud to have the assurance of salvation. This complicated deviation of theology would seem to haunt my parents every path and was something they often spoke of, thrilling in the confidence of their assurance. I wonder if for my father, this assurance and confidence was like a carrot constantly sought after, always just outside his grasp.

For me, this assurance and confidence certainly was a carrot. Who knew that a carrot could be a wicked master? While the rest of my world seemed to operate with complete conviction and assurance, I watched in bewilderment and confusion. Repenting once for a particular sin was never enough; I repented ten times, just to ensure I got it right at least once. Accepting Jesus into my heart was something I did daily. Yet, this absolute certainty everyone spoke of seemed to elude me, and I felt like I was constantly walking a thin tightrope across hell.

About ten years into their marriage, my father found himself in trouble with the church. This trouble would be termed as a moral failure. This failure called for church discipline and he was excommunicated but soon repented and was eventually restored to good standing. Shortly after, he determined that he felt God was calling us to move to Paraguay. He packed up his five children (with my mom seven months pregnant with my sister, child number six), and we followed this calling to an AMA colony deep in the jungle, known as Colony Florida.

Marilyn’s house in Paraguay

The Paraguayan government had sold plots of uninhabited land to religious groups interested in relocating to the country. A wealthy business owner from Pennsylvania purchased this colony from the government, and in turn, families from the US bought land from him. Except for a small lane running down the center of the colony, nothing was touched or cleared. As my father and the other members of the colony moved in, we had to clear the land of brush to build houses and plant gardens.

Since the land had never been cultivated, we needed to learn how to care for the soil, as well as determine the best seasons to plant the precious seeds we had brought with us from the United States.

Isolated, the colony became fertile for abuse of every kind. We were tightly controlled; females were allowed only five colors of dress: brown, dark green, dark blue, black, and gray. The colony had one cassette player shared among everyone to prevent us from being tempted by music or other distractions. We looked at other colonies with distrust, concerned about liberalness creeping into our midst.

Soon another brother was added to our family, and with nine mouths to feed, our family struggled immensely. My father planted cotton, and had two charcoal ovens, but there never seemed to be enough food or resources to go around. After three and a half years of struggle, we packed our bags and returned to Pennsylvania, hoping for a fresh start.

However, we seemed to have packed up the poverty and dysfunction we experienced in Paraguay only to unpack it once again in Pennsylvania. Our struggle to make ends meet continued. It was probably a perfect trifecta of bad luck, undiagnosed ADHD, and mental illness; but lack of resources seemed to greet us at every turn. When I finished seventh grade, my parents pulled me out of school to work for them. As the fourth child of eight, it was my responsibility to help provide for the family. School had been my safe place, where I could excel and imagine a better future. I was crushed when my formal education ended. Even then, at thirteen, I promised myself I would someday attend college.

My parents kept the money their kids earned, limiting our access to money and options to leave home. The expectation was that all the money would be given to the parents until the child was twenty. From twenty to twenty-one, the money was split 50/50. So pulling me out of school was a brilliant move. Assuming the plan worked, my parents had access to me providing both work at home, and an income from age thirteen to age twenty-one. Apparently eight years of free labor from one child seemed like an ideal plan to my parents. We had relatives who were busy doing the math, multiplying how much money my dad was receiving from each of us working and giving him the money; but to my knowledge no one ever challenged it as unethical or problematic.

When sexual abuse entered our home, there was no place to go and no resources with which to leave. I reported it to the church leaders and was quickly told not to take it to local authorities. I was then blamed and was told that in addition to being modest, it was important not to anger the men in my life. Within weeks, my parents disinherited me, telling me that I was on the path to hell and their money would never support evil like that. At eighteen, with $100 and a seventh-grade education, my life became about survival. My church leaders, without offering any support, suggested I move to another state, leaving me lost and alone. My home church told me I was not allowed to participate in communion, asked me to write a letter of confession and repentance to the church, and then would never give me a church letter when I wanted to join another church. Many in my extended family and church community were very aware of my parents’ issues and dysfunction, but were happy to hide behind the veneer of religion.

I quickly learned that the same Anabaptist communities that disavowed war and legal action in the name of peace are not particularly kind to abuse victims in their own midst. It’s easier to call the abuser to repentance and demand forgiveness from the victim than it is to navigate the murky waters of trauma and healing. Soon after moving to Ohio, the conservative Mennonite church I first attended asked me not to return, citing my clothing as too liberal. They never seemed to consider that the real issue was I was too broke to purchase groceries, let alone afford a new wardrobe; but once again I was disposed of in the name of God. Twenty years later, this church dresses more liberally than I did as a newcomer. I learned to pay attention when those in power easily change and redefine what sin is in order to suit their specific situation and desires.

To be continued…

How an Amish Boy Became a Physicist, Part 1

Today I bring you the amazing story of Leon Hostetler’s educational journey that took him…

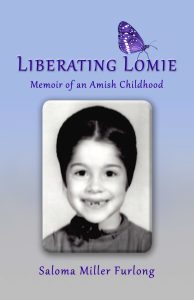

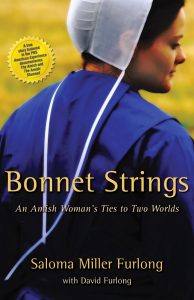

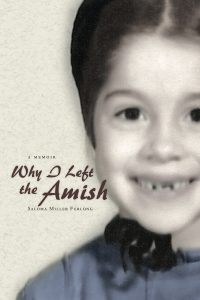

To order a signed copy of my book(s), click on an image below. You will be taken to the books page of my author website to purchase.

I look forward to reading the rest of the story. FYI, several paragraphs repeat in the middle of her story.

I had no idea you went through such trauma in your life growing up!

Hey Carol, we all hold stories don’t we? Thanks for reading. 💗

💜

[…] can read Part 1 of this story here. This is Part 2 of […]

Marilyn, Just finished your readings. I did not know of the challenged life you were presented. You are so strong, and I wish our support could have surrounded you during those times. Thank you for sharing your strength with moving forward, and courage…these readings will help others. God Bless